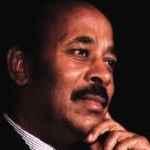

Yusuf Al-Azhari spent six years in solitary confinement as a political prisoner. Now he is helping to bring Somalia's warlords together. Michael Smith tells his story:

Yusuf Al-Azhari was walking between two Somali villages recently when he found a woman lying under a tree with her four children. She had malaria. He laid her head in his lap and she died four hours later. He took the children to the nearest village, a kilometre away, gathered the villagers together and found families to take them in.

Countless other children are not so lucky in a nation still in a state of anarchy following the collapse of its Marxist government in 1991 and an all-out civil war. For the past six years there has been no government or judiciary; schools and hospitals are closed, disease and famine rife; children die of malnutrition; and warlords fight for control of the capital, Mogadishu.

Al-Azhari is one of a network of peacebrokers among the intellectuals, religious leaders, businessmen and the women who are bringing together the warring clans in sustained dialogues for reconciliation. A former diplomat and senior administrator, he now describes himself as a `peacemaker and reconciliation promoter'.

Recently, the reconcilers spent four months bringing together clans that were fighting each other in the southern port of Kismaayo. For 28 days, their leaders sat under a tree `without accusing each other' until they reached an agreement. `We prefer to call the clan leaders 'peace lords' in a psychological bid to tranquillize them,' says Al-Azhari. `Now there is no civil war in Kismaayo. What we are trying to do next is to form a reconciliation conference, either in Somalia or outside.'

It is a dangerous task. At one point, 22 peace negotiators were rounded up and shot. Al-Azhari was one of only three who survived. He had two bullets taken out of his thigh; one remains embedded in his leg.

Contrary to world media perception, Al-Azhari says the UN's abortive peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention in Somalia in 1993 was a net benefit to the nation. It ended the worst of the civil war and created a climate in which the warlords, leaders of Somalia's six major clans, were willing to sit down and talk. Where the UN, and the US forces involved, went wrong was in attempting to arrest such warlords as General Aidid, at a time when the nation had no legal framework to bring them to book. Instead, the UN's action merely elevated their status.

In the absence of the UN, much of the drive for peace is coming from the women who have seen their families butchered on an horrific scale. A UNICEF report says that some 40 per cent of Somalia's children are believed to have died or are completely disabled, physically and mentally.

Al-Azhari brings to this work of reconciliation his faith as a devout Muslim, his years of experience in diplomacy, and his personal experience of repression. For six years in the Seventies he was held without trial in solitary confinement.

Yusuf Omar Ahmed Al-Azhari was born in 1940 into a wealthy family. He took his doctorate in political science and international law at Mogadishu University, and married `the best girl in town', Kadija, the daughter of Prime Minister Abdu Rashid Sharmarke, who later became the second president of independent Somalia. Al-Azhari was appointed senior diplomat in Bonn and then Ambassador to the USA.

Somalia, with its strategic access to the Red Sea from the Horn of Africa, became an increasing focus for the cold war between the superpowers. In 1969, Sharmarke was assassinated and five days later General Mohammed Siad Barre came to power in a Soviet-backed coup. His regime was to become one of the world's most oppressive.

Al-Azhari is uncompromising about the part that corruption played in discrediting capitalism and democracy. He cites Western construction companies, brought in to build 30 schools, who offered so many `commissions' to officials that only three schools were built. `The people turned to the socialist-communist system in reaction,' he says.

Summoned home from Washington, he was soon arrested, under `emergency security measures', and imprisoned for four and half months. He was transferred to a military camp to be trained in Marxism for nine months, before being sent to work as a farm labourer.

Passing all these tests, as he puts it, he was appointed Director General at the Ministry of Information and National Guidance. `I was supposed to orientate the public to the principles of scientific socialism,' though he remained suspect to the regime. He held this post for nearly two years, during which he was offered scholarships in the Soviet Union, East Germany, North Korea and Cuba, `all of which I managed somehow to decline'.

In 1974, he became Ambassador to Nigeria, covering seven other West African nations. At a reception in Lagos for a large Soviet delegation, Al-Azhari queried why such a high level delegation had come to a capitalistic country, `when they always tell us that capitalism is evil'. His question may have sealed his fate: within two weeks he was recalled to Mogadishu.

A year later, he was asleep with his wife and four children when soldiers burst in at 3am and seized him. He was handcuffed, blindfolded, thrown into a Land Rover and taken to a prison 350 km outside Mogadishu. It was built by East Germany to Stasi specifications: a cell three metres by four, where Al-Azhari had `no one to talk to, nothing to read, nothing to listen to'. And `to remind me that I was not a tourist in that cell', the guards tortured him daily, both physically and psychologically.

He was one of thousands swept up in the purge. Many died, were driven mad or disabled. He too reached the point of madness: `I was full of anger, hatred and depression. I was completely dehydrated, all skin and bones. I lost half my weight. It is painful to recall.'

One evening, several months after his capture, he knelt down in despair and prayed: `God, if you are truly there, help me to have peace within myself. Give me a vision of the good purpose you have created for me.' He remained on his knees for eight hours. `They felt like eight minutes. When I got up at 4am I felt light in body and soul. I had no fear. Instead a cool air of love and forgiveness had been planted in my heart.'

His guards, who had enjoyed baiting him, thought he had gone mad when he greeted them in the morning as `brothers'. From that day on, Al-Azhari ordered his day into a routine: half an hour for jogging exercise; half an hour for breakfast; the rest of the day for reviewing his life. `In the evening I was soaked in prayer from 5pm till I went to bed.' As well as a sense of God's presence, which never left him, he also found comfort in his `friends': an ant, a cockroach, a spider weaving her web, and a lizard.

The guards threw mutilated rats into his cell to indicate the fate that he might suffer, and shone bright lights on him at night to keep him awake. Yet the punishments ceased to touch him. `I felt happy and free,' he insists.

Once he was handcuffed for 48 days, the irons cutting into his wrist. His whole forearm became swollen and infected with maggots and puss. When he refused to have his arm amputated, the prison doctor shrugged, believing that he would die anyway. The guards removed the handcuffs, and Al-Azhari was able to squeeze out the infection. Within 20 days, the swelling had subsided. `I could move my fingers again.' But the scar remains.

Outside the jail, the Marxist nation was degenerating into economic chaos and poverty. `Barre couldn't even pay the prison guards,' says Al-Azhari. `Everyone was turning against him.' Eventually the prisoners were turned loose.

Al-Azhari made his way to Mogadishu to find his wife and family. They had been told that he had died within a week of his arrest. In the six years that had passed they had adjusted to life without him. When he arrived on their doorstep, emaciated and with a beard that fell to his knees, his wife believed she was seeing a ghost and fainted. It took her a week to recover.

By this time, the Soviet Union had begun to support the Mengistu regime in neighbouring Ethiopia. General Barre felt betrayed, as the two nations had been at war over their claims to the Ogaden region, and he switched his allegiance to America. He offered Al-Azhari any place he wanted in the government. Al-Azhari replied, `I will not oppose you, but I will do nothing to support you.' Soon afterwards Barre fled the country and was eventually given asylum in Nigeria.

Two years after his release, Al-Azhari was taking tea in a Mogadishu restaurant when a thought `dropped into my mind': `Why don't you forgive that man?' He struggled with the thought for weeks. `It tore me into pieces. How will he react if he has not asked for forgiveness?' Moreover, Al-Azhari had no money to pay for a flight to Nigeria. Barre had confiscated all his wealth while he was in prison. It seemed like a divine sign when the UN delegated him to take part in an OAU conference in Dakar, Senegal.

He found Barre in a small apartment in Lagos. Tears of remorse flowed down Barre's face when Al-Azhari expressed his forgiveness. After half an hour, Barre composed himself: `You have cured me. I can sleep tonight knowing that there are people like you in Somalia.' Barre died two years later.

Today, Al-Azhari's wife and children live in Canada. They urge him to join them. But he fears that if he goes he will not want to return to Somalia. He has also been offered a position at the United Nations in New York. But when he weighs $10,000 a month and a big office against 10,000 children who stand to die of war and starvation, he knows where his first allegiance lies.

The `good purpose' for which he prayed to God in his prison cell is to remain with his people, and to help them restore peace.

Michael Smith